A formal feeling comes

by Claudia La Rocco

You take a breath of air from wherever you are located and that air comes from the larger batch of air that includes the whole creation. -Wadada Leo Smith

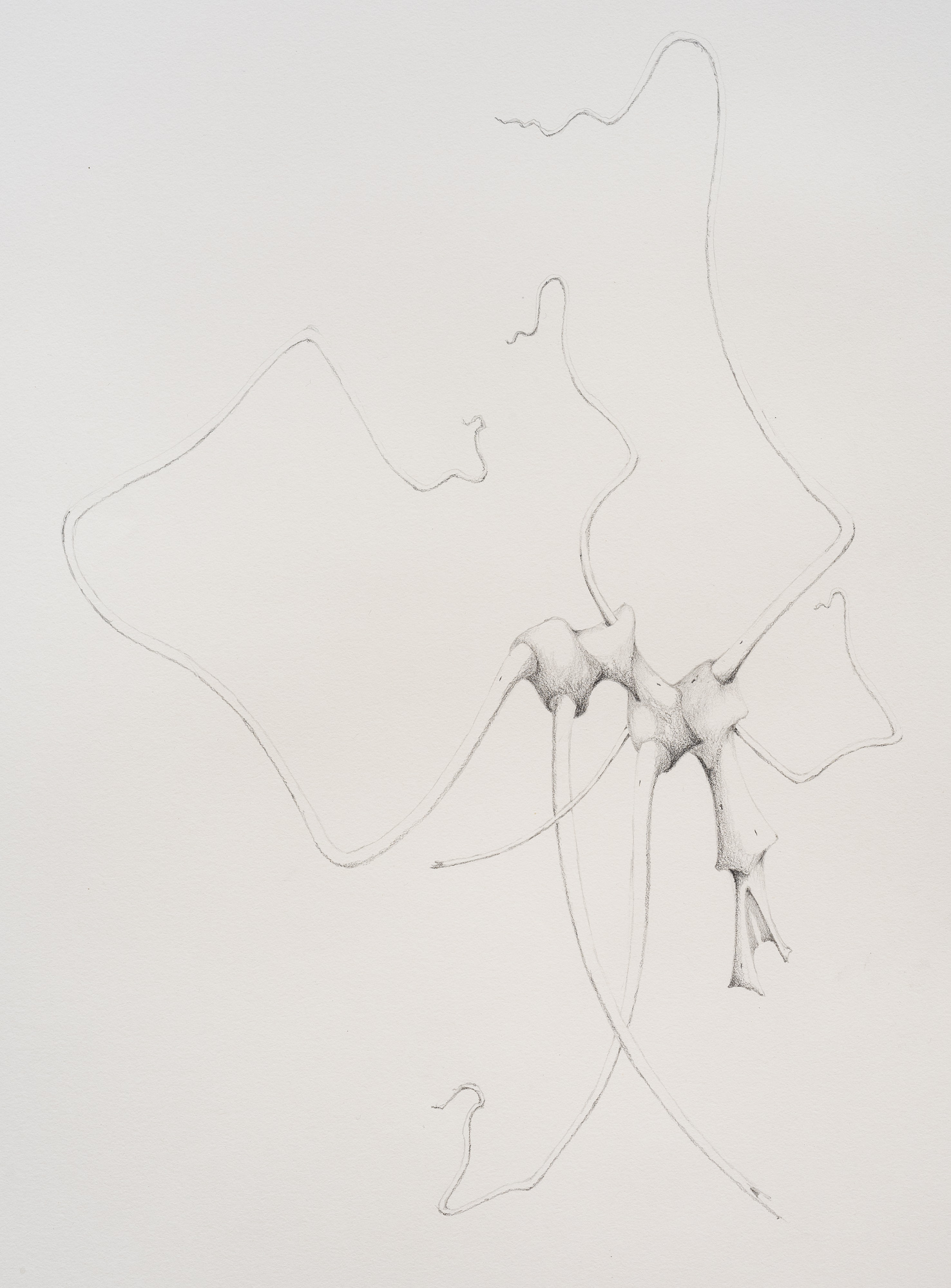

San Francisco is slouching through a typical autumn heatwave, and the second-floor room is stultifying. Framed drawings lean against the walls, surrounded by packing detritus; three larger unframed works are laid out nearby, spidery forms just visible beneath their protective translucent veils. I’m wheeling myself around on Lindsey’s studio chair, bent deep at the waist, the better to study these inscrutable graphite fragments. Willie Wayne Young has arrived at Cushion Works.

Some of the elements are recognizable — as mushrooms or acorns, construction materials, and always bones — but the worlds Young conjures are ultimately fantastical. And yet his subject matter doesn’t evolve, as you might expect an imaginative world to do. Not that it’s static, by any means — there are variations and shifts from one drawing to the next and distinct series within the larger body of work. But the strong sense I get is of a particular reality represented as exactly as possible, of something seen rather than invented. The selection at CW (which is just a small sampling of his prodigious output) covers a thirty-four-year span, so that the spare, delicate works in aggregate take on a conceptual monumentality. The longer you study the ordinary, the stranger it becomes.

I think of the unfinished, abandoned alien grandeur of Arcosanti in the Arizona desert. I think of the tracking bug Agent Smith inserts into Neo in the first Matrix movie, all articulated joints and madly seeking antennae, a not-right mix of the organic and the robotic. I think of the floating worlds sketched by Mark Kistler on The Secret City show I watched after school on PBS. “Draw draw draw!” he would exhort us. I don’t think of Dalí, but I gather Young does, and when I look up the Spanish artist’s Assumption with Rhinoceros Horns I see those same oxbow curves, lines morphing into shapes. Everything itself, everything in a state of becoming.

It’s so hot and still I have to keep taking breaks, the way a certain temperature claustrophobia often pushes me out of a sauna. At one point I wander into the adjacent gallery and encounter a gorgeous selection of paintings by Brett Goodroad and Grace Rosario Perkins — the color! the volume! the mass! Such lusciousness overwhelms after time spent concentrating on Young’s rarified world.

Phillip has a great memory of being out at a diner with Wadada Leo Smith the morning after a gig. Their food arrived and Smith’s response was immediate, adamant: “I can’t eat this. There’s no space on the plate.” No room to maneuver. I can imagine certain musicians playing these drawings as graphic scores; or maybe what I mean to say is that, for all their exactitude and restraint, they possess no small amount of possibility. Of drama, of narrative — whatever it is, the stakes feel high. Jordan had sent me a photograph of Young drawing, a close up of his fingers grasping a Staedtler pencil. It has been whittled by pocket-knife into a precision weapon, its wicked point tracing a barely discernible line. I picture his other hand holding the magnifying glass up to his glasses. I think of Emily Dickinson, another glorious obsessive, lines stripped of connective tissue, so that they might provide space for immensities.

Sweat traces a line down my back. Heat allows you to feel your body in a particular way, the weight and heft of flesh and bone. Young’s skeletal remains have been eaten away or snapped off like wishbones. The tentacles curl but they also angle, as if holding tension or encountering resistance, hardening in real time. In one sequence they’re particularly baroque, the ribs now undulating like strands of a thicker substance squirted into water, blood vessels or barnacle limbs snaking through their environments, sensing instead of seeing.

Where’s the rest of you? I wonder. But that’s not for me to know. And in truth, what’s here is more than enough.

◒

A few days after visiting Cushion Works, after the heat has passed, I come across a Vimeo “teaser” from Tanner Hill Gallery for a documentary on Young; it’s from 2015, and I don’t see evidence of any longer film having been made. The mostly wordless fragment offers various scenes from Young’s daily life in Dallas, Texas, including him drawing while on a break at the barbershop where he works. Sometimes drafting, sometimes gazing out the large storefront window, taking in the day. The footage reminds me of a beautiful line I read the night before in Michael Perry’s book Population: 485, from an essay about negotiating life as a writer in a tiny, working-class Wisconsin town. Describing a dance studio built on the border of an abandoned farm, he writes, “It is an anomaly only if you think art belongs somewhere else.”

When I moved to the Bay Area, I took a job at a big, corporate museum. I remember Bill Berkson urging me to channel the lunch-poem ethos of Frank O’Hara, who famously could compose anywhere, and write on company time. It didn’t work; I never could make anything alive in that place. But I like thinking of at least some of Young’s drawings as lunch drawings. O’Hara and Young do not, at least for me, occupy the same artistic universe; I can’t even see their art meeting in the multiverse. But the combination of concentration and ease needed to sit in the whirl of the world and distill your experience into a finely honed line, to transform the everyday into elegant event — that they share. And that’s no small thing.

Now I am imagining the opening of this show, when the room will no longer feel like a workspace, but a gallery, all cleaned up and brightly lit, full of people I know and love holding drinks and flitting about and saying awkward and funny things. I think O’Hara would like to be with us, in this vibrant art world tucked within the working machinery of a cushion factory. I imagine him writing a poem after, or maybe even during.

And then the room will be quiet again. But not empty. These drawings will remain.

◒ ◒ ◒

Lindsey is Lindsey White, Phillip is Phillip Greenlief, Jordan is Jordan Stein