Press: A New Chapter of Carlos Villa’s Career Hinges Open at Cushion Works, KQED Arts

On the Late Work of Carlos Villa: Mark Johnson, Jenifer K Wofford, and friends, Saturday, September 6, 3pm

Carlos Villa: The Code

July 13 – September 6, 2025

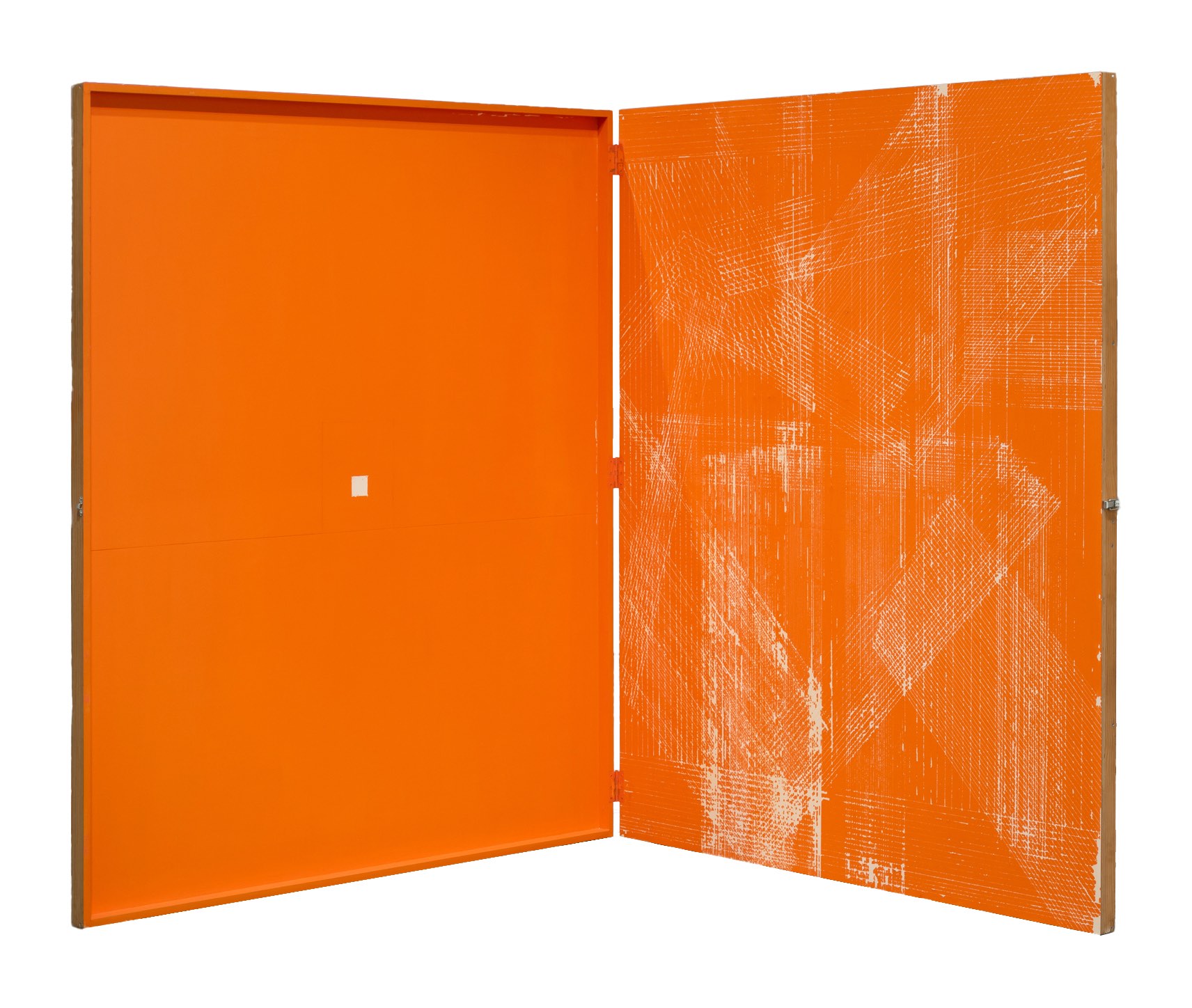

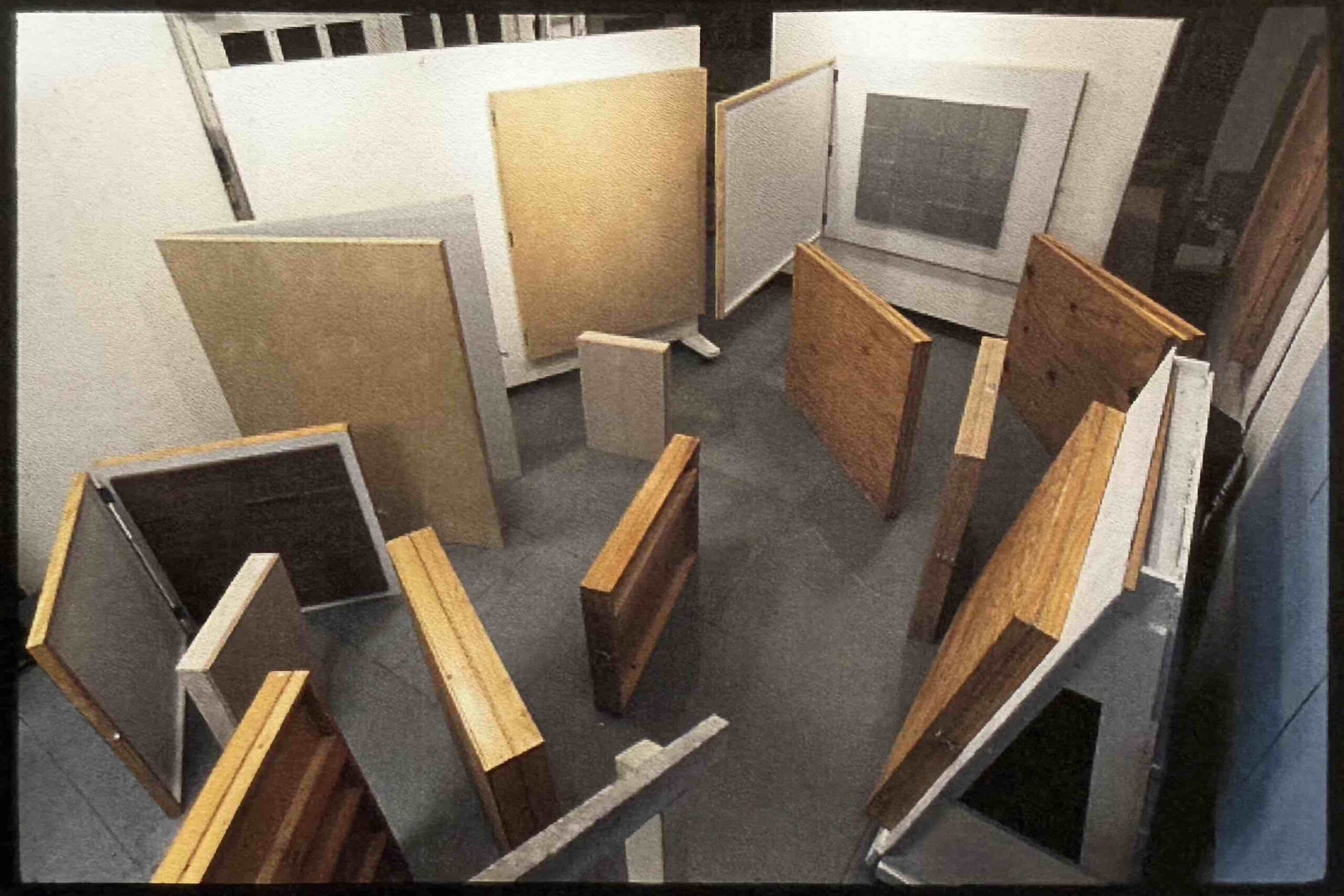

In his final years, legendary San Francisco artist and educator Carlos Villa created a suite of sculptural paintings that unfold like secrets. Hinged and heavy, most reveal a distinctive language carved in time: long lines roughly scratched through paint and wood with an awl. Other interiors are backdrops for individual canvases or grids of smaller paintings. Though equipped with cleats for wall mounting, they have no single or correct method of display. At Cushion Works, a constellation of such works are presented at various elevations and states of legibility.

The entire series appeared together only once, in a 2011 Mission Cultural Center exhibition titled Manongs, Some Doors and a Bouquet of Crates—the “bouquet” borrowed from a poem written for the occasion by Villa’s friend and colleague Bill Berkson. Like flowers, each panel opens a world before closing it away again.

Villa’s collective bouquet carries the weight of passage. The works evoke suitcases, packed and unpacked. They are maps tracing routes from Ilocos to San Francisco, charts and ledgers documenting literal and metaphorical movement. As architectures, they transform single spaces into multiples, obstructing familiar pathways while defining new ones. They are the oversized pages of impossible books, theatrical sets awaiting their performers (or have they just left?), props in stories still being written. They are trees playing coy with their rings.

The Code embodies both a return and a transformation. The works on view echo the geometric abstraction he explored in mid-1960s New York, where the young artist built relationships with peers like Brice Marden while maintaining what was apparently the city’s most extensive rolodex. Yet these late works also carry his growing disillusionment with Minimalism, 1969 homecoming to San Francisco, and radical turn toward incorporating unorthodox and found materials like blood, shells, mirrors, hair, and feathers.

It was the dawn of multiculturalism, and the Bay Area was a hotbed of activism from San Francisco State to Cal Berkeley to Alcatraz. “Shocked to be told that there was no Filipino art history,” as Lucy Lippard notes, “he became an aesthetic ethnographer and began to create it.” For the next several decades, Villa activated an array of transcultural, non-Western signifiers, retaining a view of connectedness free from the absolutes of authenticity and promoting the fluidity of migration. Ritual, performance, and “archivist activism” took hold, and he made the work that would define his reputation as the most celebrated Filipinx artist in America.

But The Code is no simple return to form or forms. Many pieces are nearly anti-visual in their indeterminacy, their hinges concealing slashes and scores carved not just with tools but with the accumulated reality of age, longing, indexing, commitment, and exhaustion. They are process and evidence-based, heavy in every sense—physically cumbersome to move, conceptually rich and mysterious to contend with, and emotionally dense with the tracks of a life crossing boundaries and marking new territories for art, restraint, and connectedness.