This text was written by Cushion Works to compliment Rafael Delacruz: Xerox, on view from April 21 to June 8, 2024.

◒ ◒ ◒

This text was written by Cushion Works to compliment Rafael Delacruz: Xerox, on view from April 21 to June 8, 2024.

◒ ◒ ◒

The Xerox Holdings Corporation was founded in the early 20th century as The Haloid Photographic Company. In the late 1950s, Haloid hired an academic to rename the company and the word “xerography” was born, a neologism that roughly translates to “dry writing” in Greek. Haloid changed its name to Haloid Xerox and then to Xerox Corporation in 1961.

Xerox made unbelievable amounts of money, acquired several other businesses, and built a brand on aggressively marketing ideas of simplicity, productively, and efficiency. So successful, in fact, was the company, that the word “Xerox” transcended its copyright, and like other trademarked products, including Band-Aid, Kleenex, Velcro, and Sharpie, its name has fallen into what’s called genericization: To Xerox is now to photocopy. Counterintuitively, this comes at a potentially catastrophic price for the company, who strongly objects to the proliferation of their trademark: If the courts determine that “Xerox” has indeed eclipsed other brand names that effectively perform the same task, their trademark evaporates. They have therefore embarked on a campaign to dissuade the public from using their name to describe the photocopy process, and the broader, non-proprietary noun and verb it describes.[i]

Rafael Delacruz titled his new exhibition, Xerox, after his broader process of thinking and making, but there’s something resonant about this ludicrous and deeply American corporate charade. He’s poking the bear, widening the generic lens—toying with the “original” and cruising the awkward turf between the intentional and the happenstance in a practice that employs a kind of xerox logic.

Delacruz is often drawing, photocopying drawings, and cutting photocopies together to make new drawings. There’s a folder on his phone called “xerox dream” which holds these images, and it’s a eclectic collection that might one day be a book—no originals and all originals. His process makes you wonder about what we call source material, and you get the sense that his mind is an active photocopy machine, imprinting influence and inspiration to generate new and unpredictable results.

Delacruz’ new paintings are works within works; the interior sections are rendered separately from the larger painted “frames” and then carefully nested within. The smaller paintings are nearly drawings, and very intimate. The larger “frames” incorporate broader strokes and an engagement with the canvas as a texture and material. (All this despite the fact that he literally painted them without a center.) And while their content is largely abstract, all sorts of things are visible: sunflower, lightning bolt, DNA, necklace, rope, placemat, remote control, sidewalk, chili pepper, feet, shoes, pants, angel, smoke, firework, pretzel, camera. It’s as if the outer painting is a thought bubble of the inner painting, a structural way to contain not only their physicality, but also their thinking. Or maybe it’s the other way around, that the smaller paintings are the thoughts within the larger bubbles. Either way, one dreams the other.

The paintings hang on a tall wooden backdrop covered in gray canvas. Their functional and invisible trade show architecture is betrayed by irregularities in canvas color and the un-ironed ripples and folds in its surface. Trade shows are exhibition-esque engagements where companies showcase new products, where originals are irrelevant, and where the promise of making copies—the more the better—is often the big idea. For this installation, Delacruz dyed large pieces of drop cloth in black bean juice then hung them out to dry. As in past works, he was interested in using “natural” materials that are culturally loaded in rather innocuous ways to achieve unknown results. This show is not about beans. In fact, he didn’t quite know what color he’d get, though he anticipated, well, black. That the drop cloths turned gray—generic but simultaneously idiosyncratic—mimics the ways in which Xeroxing changes colors, tones, and densities. As Delacruz says, “it’s as if I took black beans and ran them through a xerox machine and copied their color over and over.”

Xerox is a contingent technology, defined by sameness and chance, and black beans are just one piece of the indefinite puzzle, a conceptually non-conceptual red herring that might have you believe this exhibition concerns cultural identity, appropriation, or even assimilation—things that Delacruz happens to be interested in.[ii]

The installation also includes two framed photographs by Seiichi Furuya, and a video-projected slideshow depicting each page of his bookxMémoires 1995 (Fotomuseum Winterthur, 1995). Delacruz is drawn to Furuya’s photographs because they make him want to draw; the drawings in turn make him want to paint, and the paintings often make him want to do other things, like make films or build installations. Furuya’s work sends him to the studio, which is maybe the highest compliment one artist can afford another.

Furuya was born in Japan and has been based in Graz, Austria, for several decades. Despite the fact that he’s shown widely across Europe and published dozens of books, he’s relatively unknown in the United States. Delacruz came upon Mémoires 1995 nearly 10 years ago and reached out to the artist directly; they’ve maintained an on-and-off correspondence ever since.[iii] There are two different covers of the book: One shows a boy sleeping and the other depicts a collection of pink/purple flowers shot against the sky from below. Both feel like record covers, and speak to how a broken narrative, personal and enigmatic, can be romantic, or animated via other means.

Furuya’s photographs are diaristic—they depict things he’s seen, some beautiful or revelatory, others plain or domestic. Delacruz is drawn to the anthropological, ambient, scrapbooking aesthetic, and the human poses Furuya is able to conjure or capture. The pictures live in Delacruz’ head like saved image files.[iv] At some point along the xerox-logic timeline of perpetual creation, Delcruz imagined this show, which not only incorporates Furuya’s pictures, but equates photocopy and painting—technologies that are too old and always new, dead and alive, impossibly present, generic and proprietary.

When Delacruz reported on his bean-based canvas dyeing, Furuya responded through the English translation software he uses:

“I also read with great interest your story about making painting paint from bean juice. This year, for the first time, I tried my hand at making my own adzuki bean paste or anko. It is a simple preparation, just boiling azuki beans and adding sugar at the end, but it is one of the essential sweets in Japan. As I got older, I started to miss the ‘nostalgic taste’ and challenged myself to make it myself! The result was a great success and reminded me of my childhood when I had a craving for sweets. In the process of making anko (red bean paste), the water in which the beans are boiled is discarded once, and I remembered that the water had an azuki color, which overlapped with your photos of beans in water.”

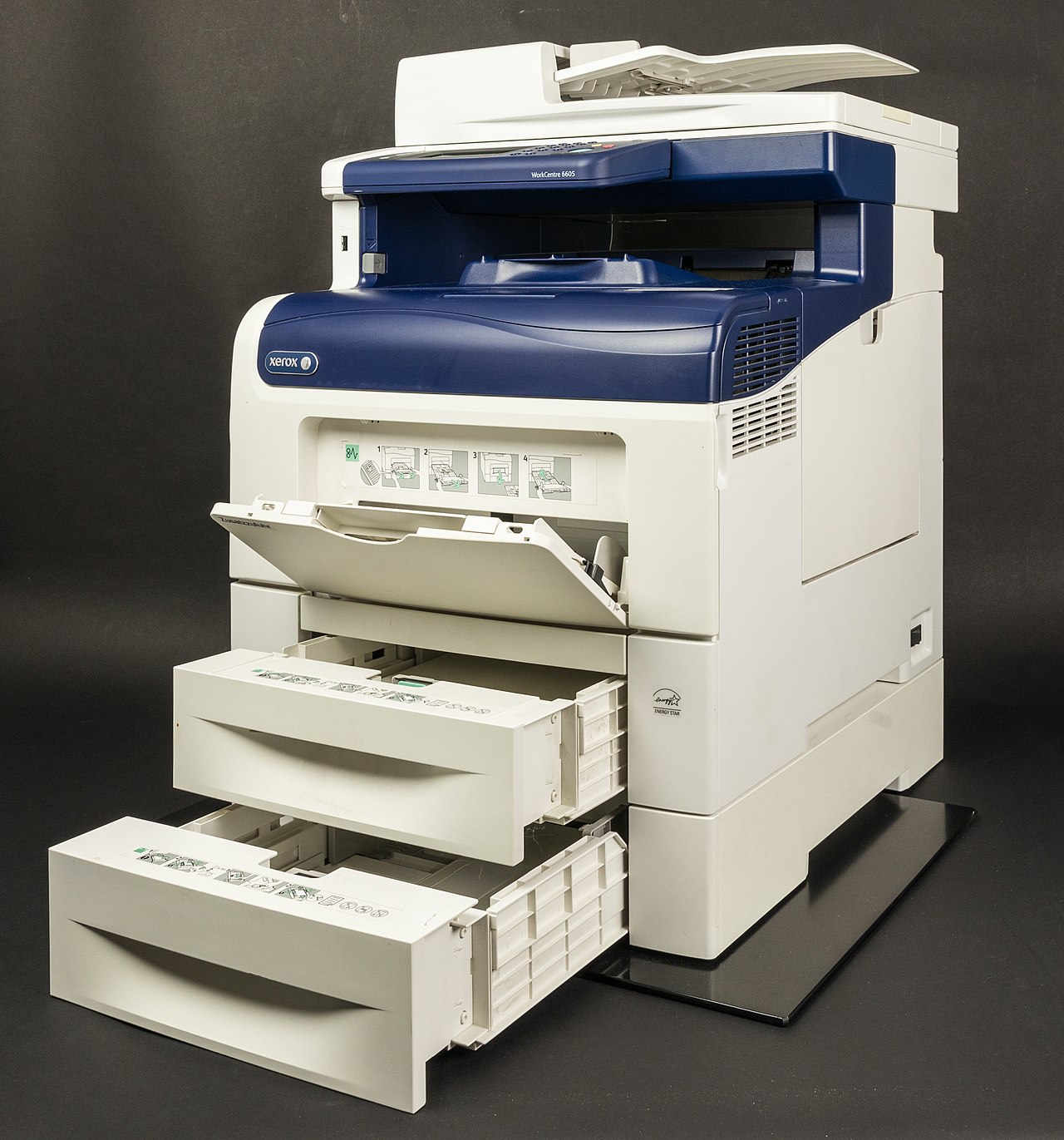

Xeroxing goes both ways, back and forth in language, time, and procedure. Come to think of it, didn’t I see one of these hulking machines buried in a painting within a painting?

Checklist

Rafael Delacruz, Stutter, 2024

Oil and colored pencil on canvas

29.5 x 33.5 inches

Rafael Delacruz, Cardboard City, 2024

Oil on canvas

29.5 x 33.5 inches

Rafael Delacruz, Steel Sky, 2024

Oil and graphite on wood and canvas

29.5 x 33.5 inches

Rafael Delacruz, Beanie, 2024

Oil on canvas

29.5 x 33.5 inches

Seiichi Furuya, East Berlin, 1986

Inkjet print

16.5 x 23.4 inches

Seiichi Furuya, Tokyo, 1994

Inkjet print

11.7 in x 16.5 inches

Seiichi Furuya, memoires 95_1920 x1080.mp4, 2024

Digital projection